The Tinny Universe: How Cast Iron Toys Influenced Early Animation

The clatter. That's the first thing that comes to mind when I think of cast iron toys. Not a jarring, unpleasant noise, but a rhythmic, almost musical echoing of a bygone era. My grandfather, a quiet man who rarely spoke of his youth, kept a small collection tucked away in his attic. I was forbidden to touch them, of course. But the muffled clang of metal on metal, the scent of aged paint and oiled iron – it seeped into my memory, a secret language spoken only between generations.

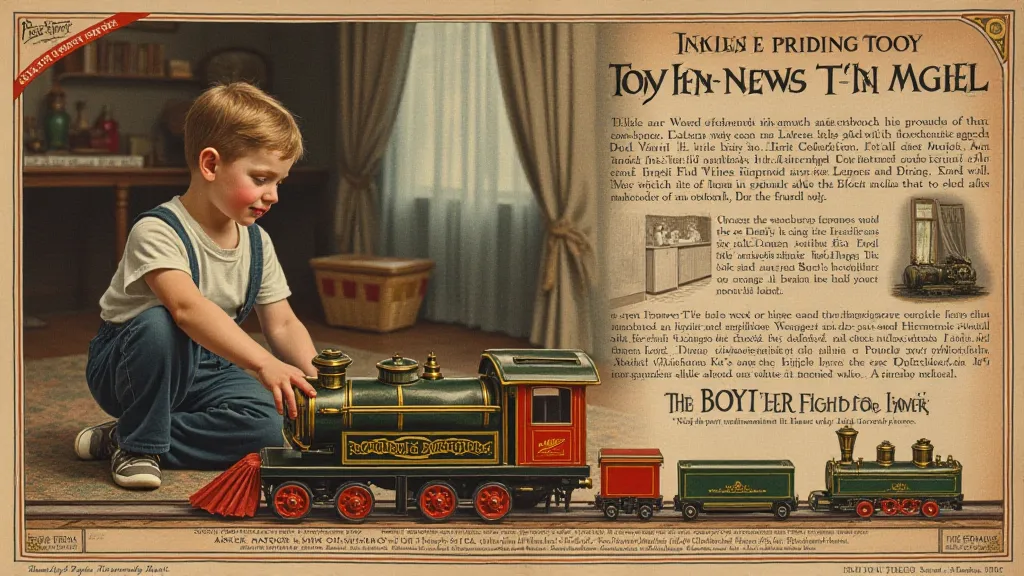

These weren't just toys. They were miniature worlds, painstakingly crafted from solid iron. Horses that pranced, fire engines that sprayed (with a satisfyingly loud rattle), and steam trains that chugged along imaginary tracks. They were tangible joys, a stark contrast to the fleeting, digital entertainment of today. And as I've delved deeper into their history, I've discovered a fascinating and often overlooked connection: the physicality and movement of these cast iron toys profoundly influenced the earliest experiments in animation.

The Rise of Cast Iron Toys: A Mechanical Marvel

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a golden age for cast iron toys. Mass production, driven by the Industrial Revolution, made them accessible to a wider audience. American manufacturers like J.W. Doll, Kenton, Whitestone, and Hubley dominated the scene, each developing their own distinctive style and specializing in particular themes – horses, cars, trains, and whimsical mechanical figures.

The manufacturing process itself was a remarkable feat of engineering. Molds were meticulously carved, often by skilled artisans, allowing for intricate details that wouldn't be possible with simpler casting methods. These molds were then used to create the iron bodies, which were subsequently painted, often with vibrant colors that have faded beautifully with time. The assembly involved a surprising number of small parts – gears, axles, springs – all carefully placed to create a functional and delightful toy.

What truly set cast iron toys apart was their inherent kinetic energy. Unlike simple dolls or wooden figures, these toys were designed to *move*. The gears and springs translated human interaction – a winding of a key, a push of a lever – into captivating motion. This focus on mechanical movement was key to their appeal and their influence.

From Clatter to Cinema: The Spark of Animation

The nascent art of animation was grappling with a fundamental question: how to create the illusion of movement? Early attempts, like flip books, relied on sequential images to fool the eye. But the mechanical toys already demonstrated a tangible, observable form of movement that sparked inspiration. Think about it – early animators weren't just drawing pictures; they were essentially trying to replicate the mechanical complexities of a cast iron train engine or a galloping horse.

The concepts of stop-motion and sequential motion, cornerstones of animation, found an early parallel in the winding mechanisms of these toys. Watching a cast iron firetruck's ladder extend and retract, or a horse’s head bobbing with each step, must have seemed like magic. This observation likely fuelled a desire to capture and recreate that magic on film.

Consider Émile Cohl, one of the pioneers of animation. His 1908 film, *Fantasmagorie*, is considered one of the first fully animated films. The jerky, repetitive movements of his character – often described as looking like a wind-up toy – bear a striking resemblance to the rhythmic movements of a cast iron toy. It's not a direct imitation, of course, but the underlying principles of sequential motion and deliberate jerkiness are clear echoes of the mechanical world that surrounded him.

The precision and predictability of the toys also influenced early animation techniques. Animators began to understand the importance of controlling movement precisely, of anticipating how a character would move, just as a toy's movement was dictated by its gears and springs. This understanding led to more fluid and believable animations, even in the early, experimental phases.

The Legacy in Form and Feeling

The influence wasn't solely technical. The *feeling* evoked by these toys – a sense of nostalgic wonder, a connection to a simpler time – seeped into the aesthetic of early animation. The often-crude, almost clumsy movements, initially dictated by the limitations of early animation technology, were also influenced by the physicality of the toys themselves. There’s an honesty to the jerky motion, a refusal to shy away from the mechanical nature of the process.

Today, collectors covet these cast iron treasures not just for their historical significance but also for the emotions they evoke. The weight of the iron, the patina of age, the faint echo of laughter from a child's past – these are the qualities that make these toys so compelling. They represent a time when toys were more than just objects; they were experiences, opportunities for imaginative play, and tangible connections to a shared cultural heritage.

Preserving the Past, Inspiring the Future

Restoring a cast iron toy is more than just a mechanical process; it's an act of preservation, a way of honoring the craftsmanship and ingenuity of the past. It's about recognizing the profound influence these toys had on the development of animation, and appreciating the enduring power of simple, mechanical beauty.

While a full restoration requires specialized knowledge and techniques—addressing rust, repairing cracks, and repainting—even a gentle cleaning can reveal the underlying beauty and historical significance of these remarkable objects. And just as the early animators drew inspiration from the clatter and charm of cast iron toys, today’s artists and creators continue to find inspiration in the ingenuity and simplicity of the past. The tinny universe, once a world of physical play, continues to resonate in the digital age, a testament to the enduring power of imagination and the beauty of a well-crafted machine.